Every inclusionary housing program should consider how much of a city’s affordable housing needs developers should be expected to meet. Typically, cities establish this basic requirement as a percentage of units or square footage area of each development that must be set aside to be rented or sold at affordable prices on site.

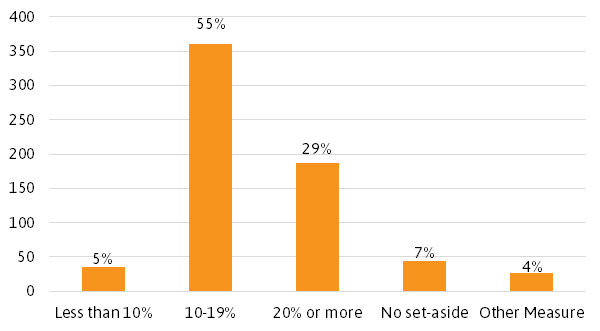

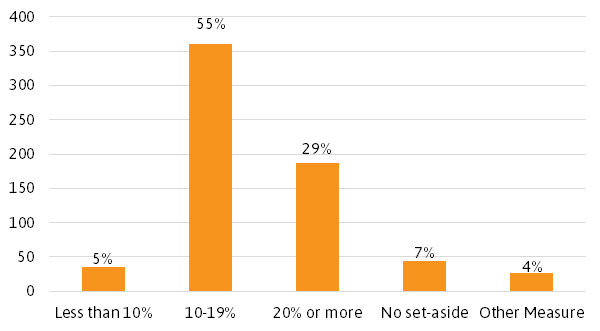

According to a 2021 study by Grounded Solutions Network, the vast majority of programs have a minimum set-aside of at least 10% of units; only 5% of programs have a minimum set-aside less than 10% of units. Also, 29% of programs have a minimum set-aside of 20% of units or more.

The set-aside requirements vary for about one in three inclusionary housing programs. The variation is based on a wide range of factors, including level of affordability, project size or density, geographic location, targeted population, tenure, percentage of open space, and case-by-case negotiations with the developer. In any case, the baseline performance option sets the economic bar against the other evaluated alternatives, so it must be appropriate for local market conditions.

Increasingly, cities commission economic feasibility studies to determine how large of a set-aside to require while avoiding financial hardship to developers.

Traditional inclusionary housing programs—which are designed around the assumption that units will be provided on site even if they allow payment of fees as an alternative—generally evaluate the economic feasibility of their performance requirements and then set in-lieu fees so they are economically comparable to (or slightly more expensive than) the performance requirement .

Most programs require the affordable units to be proportional to market-rate units with respect to number of bedrooms per unit – i.e., if the market-rate units are 60% one-bedroom units and 40% two-bedroom units, the affordable units must also be 60% one-bedroom and 40% two-bedroom.

In some communities, new market-rate multi-family development is composed of mostly smaller units—studios, one-bedrooms, and two-bedrooms. But low-income renter households of color may have disproportionately larger household sizes; for example, households of color are more likely to live in multi-generational households than White people.

Cambridge, MA’s inclusionary housing program encourages developers to provide affordable three-bedroom units. In developments of 30,000 square feet or larger, the ordinance requires the creation of three-bedroom units.

How does a feasibility study help establish an appropriate inclusionary policy?

An economic feasibility study conducted by a qualified real estate economist can provide local policymakers with a clearer sense of how inclusionary housing requirements will impact the profitability of local development projects and the price that developers can pay for developable land. The economist will research local prices and rents as well as the key factors driving the cost of building. The economist will use this information to assess whether or not proposed affordable housing requirements would make typical projects infeasible. Any kind of feasibility study is necessarily somewhat imperfect, but the goal is to give policymakers a general sense of the likely impact of proposed housing requirements and incentives on land prices and development profits. Ultimately, a detailed feasibility study is the only way to address legitimate concerns about whether affordable housing requirements could do more harm than good.

Read more about conducting an economic feasibility analysis here.

How can an inclusionary housing policy respond to neighborhood-by-neighborhood differences?

It is important for cities to be aware of market conditions when they set their inclusionary housing requirements, both for the entire city and for various neighborhoods.

Most cities do not adjust their inclusionary requirements at a neighborhood level. For cities without wide variations in neighborhood market conditions, this may be appropriate because incentives and inclusionary requirements automatically compensate for differences in market conditions. For example, it may be more expensive to build in high-cost neighborhood, but a density bonus is worth more in neighborhoods where home prices or rents are higher.

Some cities, however, have responded to concern about the impact of inclusionary requirements in certain sensitive neighborhoods by varying their requirements or incentives by neighborhood. This is called geographic tiering.

Rather than vary the requirements by neighborhood, some cities vary their requirements based on construction type. These are generally places where local market conditions make higher-density construction economically marginal enough that affordable housing requirements can become a barrier to development.

The decision to vary affordable housing requirements by neighborhood or construction type should typically be made based on the findings of an economic feasibility study . In general, a city may want to pursue these varying requirements if the feasibility study showed that citywide supportable requirements would have an adverse impact on the feasibility of otherwise desirable development in certain areas.

Why do cities have different income targets for homeownership units versus rental units?

Cities often set affordability levels higher for ownership units than for rental units. For programs with a single income targeting requirement, 23 percent of programs set the maximum income at 81 percent of AMI or above for homeownership developments, compared to 11 percent of programs for rental developments. This pattern is consistent for programs targeting multiple income groups, which tend to have a higher percentage allocation in extremely low- and very low-income levels (50 percent of AMI or below) for rental units than for homeownership units. Data source: Wang and Balachandran (2021)

This policy is often dictated by market prices. For example, a household earning 80 percent of AMI may be able to afford the rental price for a median priced one-bedroom apartment, but cannot comfortably afford to buy a home. Pricing ownership units at 80 or even 120 percent of AMI meets this need. However, inclusionary rental apartments with their price set to be affordable for a household earning 100% of median income would often be the same price, or even more expensive, than regular apartments for rent in the area, so they aren’t necessarily serving a critical housing need

On the other hand, ownership units typically cost developers relatively more to produce. While it would be possible to require that developers price ownership units so that they serve the same income group that is being served in rental housing, this would have a greater impact on financial feasibility for ownership projects. Many cities have determined that allowing developers of ownership units to serve a higher-income group can reduce the burden of the program on ownership projects while still serving a real affordable-housing need.

What is the best way to set the level of a linkage or impact fee ?

Generally communities commission a nexus study to determine the extent to which new development (residential or commercial) contributes to the need for affordable housing. They use the results of this study to determine the exact dollar amount of any linkage or impact fee .

Residential linkage fees can either be a set price for each new home or can be calculated based on the square footage of the new home. On the lower end, Mountain View, California charges new residential development $10 a square foot, while Santa Monica, California charges approximately $28 a square foot. Berkeley, California charges $28,000 for each new market rate home to fund affordable housing.

Boston, Massachusetts has one of the oldest commercial linkage programs in the country. It charges new commercial development over $8 a square foot. From 1986-2000 Boston generated $45 million in linkage fees , which funded nearly 5,000 units. * Arlington County, Virginia also has a commercial linkage fee of $1.77 a square foot, which was expected to generate almost $14 million in revenue between fiscal year 2013 and 2016.

Commercial linkage fees often vary depending on the type of development (office, hotel, industrial). For example, Menlo Park, California charges almost $15 a square foot for office developments and just over $8 a square foot for industrial and other uses.

Why do a feasibility study ?

When considering whether to adopt or revise an inclusionary housing policy, local government agencies often retain an economic consultant to prepare a feasibility study . This study evaluates the economic tradeoffs of requiring a certain percentage of affordable units in new residential or mixed-use projects.

Feasibility studies help policymakers assure that new policies and programs are economically sound and will not deter development, while still delivering the types of new affordable units needed by the local community.

Feasibility studies are different than nexus studies, which are a similar type of analysis often used by local jurisdictions to establish residential or commercial linkage fees to fund housing programs. A feasibility study determines how a new inclusionary policy would affect market-rate housing development costs and profits. A nexus study quantifies the new demand for affordable housing that is generated by new commercial or market-rate housing development.

What goes into a feasibility study ?

While every study differs based on the needs and market conditions of the specific area, in general they follow a similar outline:

How should an inclusionary housing policy respond to changing market conditions?

Real estate markets are constantly changing. While inclusionary housing programs are often flexible and adaptable, they can’t respond to each and every change in the market. Some communities have increased their inclusionary requirements during housing booms and reduced them or waived them entirely when their markets crashed. However, it is in general difficult for cities to time the market and adjust their inclusionary requirements every time their housing markets change.

A few cities temporarily repealed their inclusionary requirements during the most recent downturn in order to avoid over-burdening projects during a fragile period. But most programs did not feel that this was necessary. * While it is far more difficult for projects to support housing requirements during a downturn, most projects wouldn’t move forward in these times even without affordable housing requirements. Waiving requirements temporarily does little to promote development, but it risks missing the opportunity to produce affordable units when the market unpredictably returns.

It is possible that these temporary waivers helped speed up the market recovery in these cities, but it did so by permanently exempting certain projects that would have been built slightly later without the waiver.

When the market is soft, cities don’t waive fire codes or other zoning requirements, even though they too could help some projects pencil out sooner. Instead, they wait for the market to recover because these are appropriate minimum standards. If housing requirements are modest enough that they are not economic barriers to development most of the time, there should be no need to adjust them for market cycles. On the other hand, if a community experienced a permanent change, like the loss of a major employer that changed the likelihood that rising housing prices will ever again be a challenge, then certainly adjustments to affordable housing requirements would be appropriate. Some communities plan on comprehensive reviews of their policies every 5 years including an analysis of whether inclusionary requirements remain appropriate given longer term economic trends.

For programs with in-lieu fees or housing development impact fees , frequent review and adjustment is important. Many cities have written specific dollar amounts into their ordinances for these fees. Over time, a fixed fee will drop relative to inflation and relative to the cost of providing affordable housing. Some communities have managed to keep their fees up to date by having their council annually approve a change to the fee calculation. However, because this is a controversial issue, these annual approvals can be challenging. In response, a number of communities have indexed their fees to allow for regular increases (and potentially decreases) in response to changing market conditions. For example, San Francisco increases its in-lieu fee schedule annually based on the change in the Engineering News Record Construction Cost Index for San Francisco. Other cities tie fee increases to changes in the Consumer Price Index or a local housing price index.

How can communities with soft or mixed housing markets implement inclusionary housing?

New market-rate development tends to occur in high-opportunity areas from which people of color have been systematically excluded and are often unable to afford. In communities with stronger housing markets, inclusionary housing is an effective tool to provide affordable homes in high-opportunity areas. But in communities with less strong housing markets, it may not be financially feasible for developers to include affordable units in new market-rate development.

This article describes some approaches that communities can take to craft an effective inclusionary housing program early in the market cycle, or in mixed markets where one neighborhood varies dramatically in rent levels from the next.